Abstract

Women in rural areas make up almost 43% of the agricultural workforce in developing countries, but a lot of their work remains unpaid, unreported, and not recognised. This article critically analyses the socio-economic aspects of women's contributions to agriculture, particularly in terms of wage systems, the collection of data, and the coverage of the law. From a gender perspective, it calls attention to systemic inequalities based on patriarchal norms and unequal land ownership, advocating for policy reform and structural acknowledgement. By making their "invisible" labour visible, we stress the imperative of inclusive development frameworks that place women's agency at the forefront of agricultural economies.

Persistence of Problem

Even as they form the backbone of rural agricultural economies throughout the Global South, women are still made invisible in the formal discourse of development. They plant seeds, reap harvests, tend livestock, and provide household food security often at the same time. These diverse contributions are habitually omitted from national statistics, development frameworks, and systems of wages. The structural invisibility of women's farm work is not just a failure; it is the result of deeply rooted patriarchal norms, legal marginalisation from land rights, and the inability of institutions to observe and uphold gendered roles in the agrarian economy (Agarwal, 1994; Doss et al., 2018). Unpaid work is a fundamental but lesser-spoken concern. Women worldwide do three times as much unpaid labour as men, with even higher proportions in rural agricultural areas (FAO, 2011). Central farm activities such as weeding, saving seeds, and post-harvest activities are seldom paid or formally acknowledged (Mehra & Rojas, 2008). This invisibility denies women extension services, credit, and technology since they are not likely to be registered as 'farmers' (Quisumbing et al., 2014).

Structural discrimination deepens this marginalization further: 13% of landholders in agriculture are women in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (World Bank, 2022). Without their rights to land, access to credit, subsidies, and policy voice is heavily restricted for women (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). Cultural stories also contribute to women's invisibility in farming. In India, for example, rural women are frequently described as "farmer's wives" but not as farmers themselves, even when they undertake most of the work in agriculture (Kelkar, 2009). Semantic erasure at the level of words matters for policy perception and undermines the socio-economic validity of their roles. Moreover, seasonal migration and male outmigration for urban jobs have resulted in the 'feminisation' of agriculture in most areas. Nevertheless, this transition has not resulted in increased rights or acknowledgement for women but rather contributed to their burden without structural assistance (Lastarria-Cornhiel, 2008). The issue is also intergenerational. Rural girls commonly socialise into these roles at an early age and absorb farming and household duties that constrain their schooling and participation in the economy (UN Women, 2020). This becomes a cycle of dependency, low productivity, and chronic poverty, further fuelled by climate stress, land degradation, and unstable markets, all of which disproportionately affect women because they have little adaptive capacity. In the global development debate, silence is deafening on women's farm work. Visibility is not only a question of justice but productivity and sustainability. It has long been CDPP's argument that inclusive development must start with grassroots visibility, agency, and access.

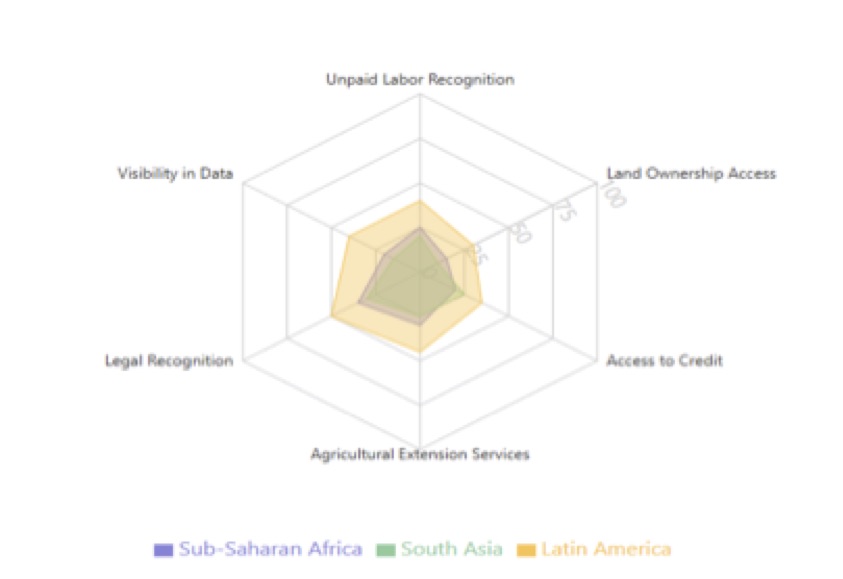

Figure 1: Multidimensional Invisibility of Women in Agriculture

Source: The information used for this graphic was tabulated from FAO and World Bank sources, namely Slavchevska et al. (2020) and Manfre et al. (2013).

Figure 1 is a radar chart comparing the multi-dimensional circumstances of rural women in agriculture between three regions: Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. The chart assesses six key indicators-recognition of unpaid labour, access to land ownership, credit access, access to agricultural extension services, legal recognition, and visibility in data-on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher values representing more positive circumstances for women. The graphic clearly indicates that Latin America does better in all six indicators, reflecting stronger legal frameworks and institutional support for female farmers. Sub-Saharan Africa performs moderately, and South Asia has the worst performance, particularly in areas such as ownership of land and the acknowledgment of unpaid labour. This difference reflects the structural barriers and neglect at the systemic level that continue to keep women marginalized in the agrarian economy, particularly in South Asia. The chart reaffirms the article's advocacy for gender-responsive policy reform by bringing out into the open the deeply embedded disparities in farming systems.

Move toward Recognition, Rights, and Resilience

Addressing the invisibility of rural women in agriculture requires more than skin-deep interventions; it needs a fundamental change in agricultural economy thinking, recording, and support. It must start with the data. Most national agricultural censuses and surveys do not disaggregate gender or misreport women's participation because they use culturally determined definitions of a "farmer" (Slavchevska et al., 2020). There needs to be a policy transformation that requires sex-disaggregated farm data as the foundation for development planning. More than mere inclusion, the datasets need to reflect the varied, usually informal, and unpaid work by women that is not covered in traditional economic models. The most revolutionary solutions include legal and institutional reforms in land rights. Secure land tenure not only improves women's social standing but also raises farm productivity, access to credit, and investment in long-term conservation (Ali et al., 2016). Rwanda and Ethiopia have shown that joint titling and property law reforms respecting women's inheritance rights strengthen household well-being and gender equality in agriculture (Deininger et al., 2008).

However, for these changes to succeed, they must be complemented by social education campaigns to break down patriarchal values and to enhance awareness of legal rights by both women and men. There must, in tandem, be an effort to reimagine agricultural extension services. Traditionally designed with the male farmer and large farms in mind, they tend to leave out women because of structural inequities, lack of time, and mobility issues (Manfre et al., 2013). Gender-responsive extension models must be rolled out through local cooperatives, self-help groups, and online platforms to reach women with information and technology more easily.

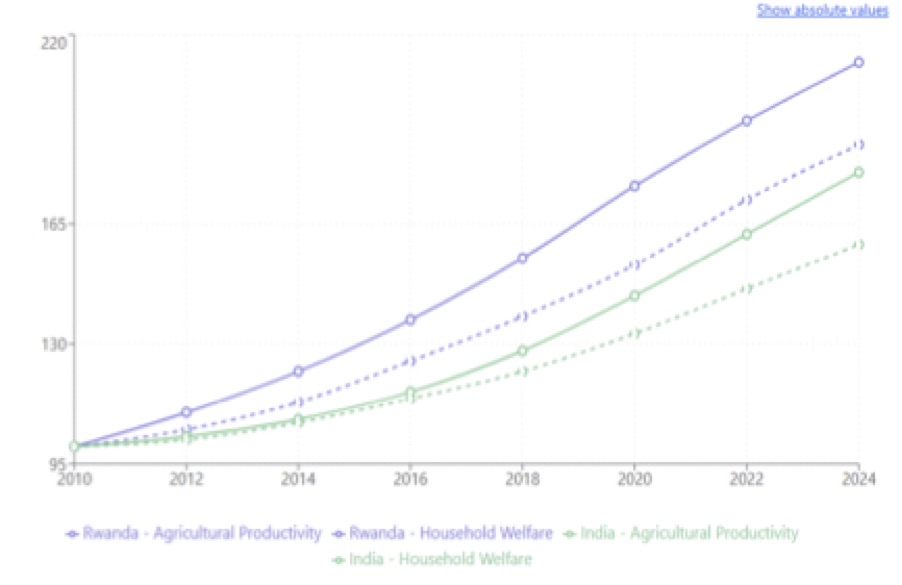

Figure 2: Impact of Gender-Responsive Agricultural Reforms

Source: The underlying data was drawn from case studies by Ali et al. (2016), Deininger et al. (2008), and GSMA (2020).

Figure 2 represents a line chart monitoring agricultural productivity and household well-being in India and Rwanda between the years 2010-2024, based on a base value of 100 in 2010. It segregates between agricultural productivity (solid lines) and household well-being (broken lines) on two colours per country-purple for Rwanda and green for India. The data indicate that Rwanda has enjoyed much higher and more stable growth in both indicators than India. The trend is indicative of the success of Rwanda's agricultural reforms that are inclusive, especially with respect to land tenure as well as gender programming, which has led to welfare gains at the household level that are more widespread. Conversely, India's gradual progress underscores rural women continued structural challenges, including constrained land rights and access to credit. The rate supports the argument in the article that the empowerment of women through legal status, access to resources, and policy voice has real development returns.

For example, mobile-based advisory services in Kenya and India have been shown to fill this gap, providing climate-smart practices and market news tailored to women's times,

and needs (GSMA, 2020). Financial inclusion is another key entry point. Women's limited exposure to formal bank accounts, credit, and insurance limits their capacity to invest in their farms or weather climate shocks. Microfinance, when supported by group lending mechanisms and savings cooperatives, has been found to be effective in empowering rural women economically and socially (Swain & Wallentin, 2009).

Additionally, gender-sensitive agricultural insurance schemes could hedge against natural risks, providing livelihood security. Financial products must be context-specific,

accessible, and for women with low literacy and mobility. Institutionally, gender must be integrated into policy processes beyond tokenism. Gender budgeting, or the distribution of public funds to address women's needs, must be incorporated into national agricultural policies (Chakraborty, 2016).

This both secures resource distribution and responds to governments to equity levels. Moreover, women must be included at all levels of farm management, from village councils to national planning organizations, so their reality matters to policy decisions. Establishing women's producer groups and rural cooperatives offers a replicable example of inclusive participation, with government support. Education of rural girls in agro-ecology, enterprise, and leadership has to be invested in if the cycle of invisibility is to be broken. Mentorship programs and local training schools can create the next generation of women leaders, and gender-sensitive education at agricultural colleges can build equity-minded professionals. Climate resilience adds an element of urgency: while disproportionately affected, women hold crucial Indigenous knowledge that is vital to sustainability (Dankelman, 2010). Policies need to put this expertise at the centre, as with women-managed seed banks and water organizations in Nepal and India. There also needs to be profound cultural transformation scheming out the old "farm wife" paradigm in favour of empowered positions as farmers, inventors, and climate decision-makers. Media and narrative have the power to reframe public stories, producing pride and visibility for women's agricultural selves. In the end, women's rights and recognition are not on the margins; they are at the centre of reshaping food systems in the Global South. Reforms of the structures must be coupled with cultural changes that view and invest in rural women as central actors in sustainable development.

References